Les Rallizes Dénudés by Jin Sato

A few weeks ago a website announced the death of Takashi Mizutani, the figurehead of cult Japanese band Les Rallizes Dénudés. The site was fairly new, and bore the URL lesrallizesdenudes-official.com. It announced that Mizutani had passed away almost two years ago in 2019 but also carried a statement announcing the establishment of a company called ‘The Last One Musique’ that included former band members, and which denounced all LRD releases except the Rivista albums. The name connected to the site’s registration was Makoto Kubota, a musician and producer who played in Rallizes in the late 60s/ early 70s. We got in touch to ask Kubota about the site and the organisation’s plans; to also ask what this activity meant, not just for the future of this most bootlegged of bands, but also for the rock & roll mythology surrounding its leader.

While Kubota has spent his life playing music, making records and producing, half a century ago his mind was opened to rock & roll through Mizutani. His first experiences in bands were in the 1960s playing bossa nova. Then in 1969 he met Takashi Mizutani and joined his group Les Rallizes Dénudés. He played with the group from 1969 until roughly 1973, with two interruptions. The first was in 1970, when he went to America to immerse himself in the rock music he had fallen in love with (he saw The Grateful Dead at a Black Panthers rally, and The Band at the Last Waltz, among many, many other shows). The second was a couple of months after his return, when he was arrested for growing and giving away marijuana.

While still in Rallizes he began recording solo and formed his own band, Sunset Gang, with whom he released a number of records and toured internationally, opening for Eric Clapton’s 1975 Japan tour. They later became Sunsetz and opened for INXS among others. Kubota stopped touring and moved full time into producing in the 1990s, and since then has worked on a large variety of projects, including curating compilations and co-producing a documentary on the disappearing traditional music of the Miyako Islands, called Sketches Of Myahk.

In the half century since their inception, Rallizes have become a legend of the underground, one about whom there are few hard facts but many rumours, especially for non-Japanese speakers. They formed in 1967 at Doshisha University in Kyoto and played heavy, hypnotic rock music typified by use of feedback and folk arrangements. Little is known about Mizutani, and tracing the history of the band’s various members can also be difficult, although one of the founders is known to have been a perpetrator of the Yodogō hijacking incident. In 1970 Moriaki Wakabayashi, Kubota’s predecessor on bass for Rallizes, assisted in the hijacking of Japanese Airlines Flight 351, an act of terrorism orchestrated by hardline communist faction, the Japanese Red Army. Armed with samurai swords and pipe bombs the gang of nine commandeered the passenger jet in order to fly to Cuba and diverted it to North Korea where they were offered asylum. It is where Wakabayashi lives to this day.

It says something that much less is known about many of his former band members who stayed in Japan and weren’t communist revolutionaries. Much of the information around the group is anecdote, rumour, or misdirection (as one unlucky Red Bull journalist found out when he tried to track down Mizutani) and few official albums were ever released, although there are tens if not hundreds of bootlegs.

Among the revelations in the long conversation with the friendly and effusive Kubota was news of his forthcoming remastering project of Rallizes’ official albums using the original Rivista masters, and discovery of a large cache of tapes in Mizutani’s room in Kyoto. Kubota also spoke about wanting to fulfil his friend Mizutani’s wishes, in working with his family to register ownership of Mizutani’s music, in order to address the bootlegging that the enigmatic frontman had hated.

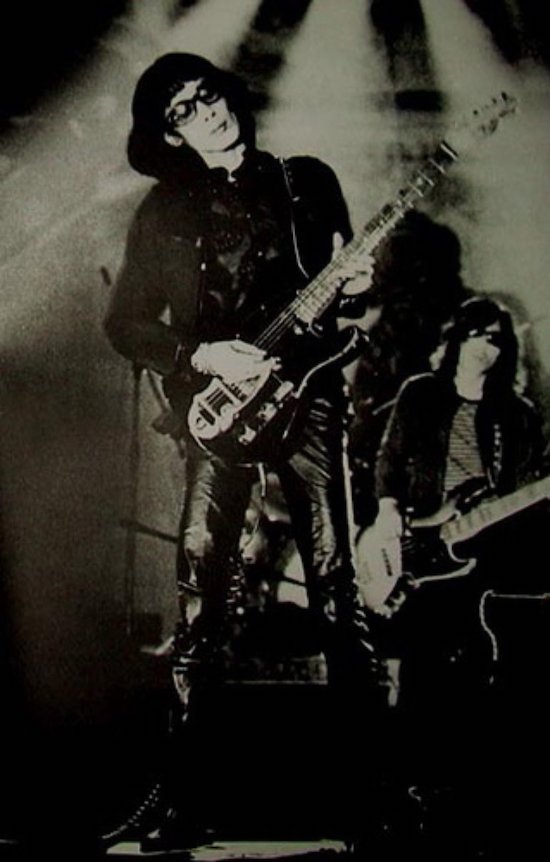

Makoto Kubota, California, 1971

Recently I came across a new Les Rallizes Dénudés website where Mizutani’s death was announced. Can you tell me what your role in this has been, and can you shed any light on the announcement of a syndicate called The Last One Musique?

Makoto Kubota: I don’t know how much I can explain, but there is a family, who [have inherited] Mizutani’s musical heritage.

Are the family who survive him making decisions and giving permission for what happens with the music now? Is there anyone else involved?

MK: Well, they depend on me for production and technical advice. They are not from the music industry so they’re not familiar [with such things]. Mizutani didn’t like the piracy of his music so this is on the list [of priorities] as number one, two, three and four. We have to register the songs, set up a company and get a lawyer to give notice to the pirate companies. So that’s what I’m doing – I’m making plans and organising the situation. The website is just the start of that. It is the only official website, saying which are the official records, and that other than that it was all piracy. This is what they want the world to know.

What did Mizutani think of the bootlegs?

MK: I asked him about all the pirates – there are more than 100, I guess. Somebody starts it, and then it becomes contagious. Somebody bought a CD, ripped it, and that makes another generation, so it’s feeding back. It was okay for the Grateful Dead because they liked the idea, but Mizutani wasn’t sure, he was very confused, and he didn’t like most of them. He said he never wanted to even listen to them, because most had very bad artwork, and bad production quality. He didn’t like the idea; he hated the idea. So, I said okay, let’s start something proper.

When was the last time you spoke to Mizutani?

MK: I hadn’t met up with him for a long, long time. I had phone conversations here and there but not much since I left the band in mid 70s – maybe there were some chats and drinking tea together a few times after that. I had become very busy with my own projects and in the 80s I was touring like mad. Finally, I quit bands, stopped gigging and I became a full-time producer around 89 or 90. Then I got a phone call from Mizutani in 91 saying he had a plan to introduce three official CDs. He asked me about the demo tape we recorded together in 1970, so this was already over 20 years later. It’s weird now, that I am mastering my own music from 50 years ago. It doesn’t sound too bad! But anyway, I got a call from him, and we had a conversation, and we were supposed to meet but somehow it didn’t happen, and after that, I didn’t talk to him again until two years ago.

Suddenly, I got a call from him. I had been sending messages to people, thinking about which guys might have a contact because I was trying [to get in touch]. One got through, and he also probably sensed that this was the time for him to start talking. I had come back from New York where I was producing a film for the legendary Japanese singer Sachiko Kanenobu. I had been in New York to shoot her last scene at Central Park, a huge free concert. The broadcasting guys and backing musicians for her knew who I was because of the Julian Cope Japanese rock book, and they asked me many questions about Rallizes. Well, this was something I never imagined – our music spreading this wide. So, that’s why I wanted to talk to Mizutani about how something needed to be done. He stopped gigging after 96, but he was still alive, and I wanted to start something with him again. Anyway, he called me and we had two months of quite frequent conversations and text exchanges. It was a big plan. I even said, ‘This might be the last one, but let’s do a sizeable tour to say hi to this younger generation who have never seen Rallizes, and the foreign followers and fans, who never had chance to see the band.’

I suggested we redo all their official records, starting from Oz Days Live. I said that maybe we should remaster the record because back then there was no idea of mastering. The mixing was very amateur… it wasn’t even mixing! It was only [a recording session with] eight microphones and one stereo tape machine. That’s all we had. I had contact with Toshiba Cutting in Tokyo and at that time I was recording my first solo album Machiboke, so I asked the record company people if they could take a client from outside and they said yes. I set up meetings for Tezuka, who’s the owner of Oz club, and Mizutani. But still, we were amateur. Especially Rallizes – we were all inexperienced.

You were very young weren’t you – aged 20 or so?

MK: Yeah, other people started early playing in bands, or entertaining American soldiers in the in the Army, playing Air Force clubs and stuff like that. But we were purely university college students so we didn’t have that.

So you were recording straight onto tape? No mixer no nothing?

MK: A simple Sony mixer with no EQ, so that’s why that record sounds as it is.

To clarify, which recordings are you remastering?

MK: I’ve completed Oz Days. Tezuka the owner of Oz told me that [it was essentially] a studio live recording. With other bands he recorded whole shows [in the club] with an audience, but for Rallizes we were only in the place for one single afternoon; only recording for three hours. He sent the tapes to me. Usually a Japanese 7-inch reel from 50 years ago would be a total nightmare. It’s magnetic tape, and the Japanese climate is lethal. Sometimes it breaks the tape machine. If it’s very sticky you put it in the oven to dry the tape and play, but that means the death of the tape. For these tapes, we were extremely lucky. I can play it back, and I didn’t need the oven. It’s a miracle. I ripped all the historic recordings onto ProTools and started mastering, and this is the result. I can’t give you the name of the label, but it’s a small American company. I also warned the label that they should be ready by December because I can’t wait, we need the momentum, and I have many other jobs! So in December I’m planning a few events, a talk event with English subtitles.

So no Taj Mahal Travellers?

MK: No, certain conditions meant we decided to delete Taj Mahal. We’re still figuring out what it should be called, but we will announce it in December. Also, I will start remastering on all the Rivista CDs, one called Mizutani, which was recorded in 1970 when I was 21 years old, my first studio recording.

Can you clarify which albums you have plans to remaster?

MK: All of the Rivista recordings. I won’t touch them too much musically, I’ll just make it more refined. Some albums I will just use the final digital master for the CD, but I have got whole generations of all four albums, from the cassette or reel-to-reel tape. And then they were transferred to 10-inch, quarter-inch reel, then they were recorded to digital audio tape, on a three-quarter inch big Sony U-Matic. They even did digital mastering in the expensive studio. I will do Studio Live 67-69 to begin with, then Mizutani, which is 1970. And then ’77 Live. So, I’ll remaster everything. But we don’t know when, or who will be distributing next year yet. I will leave the decision up to his family. I can only advise them.

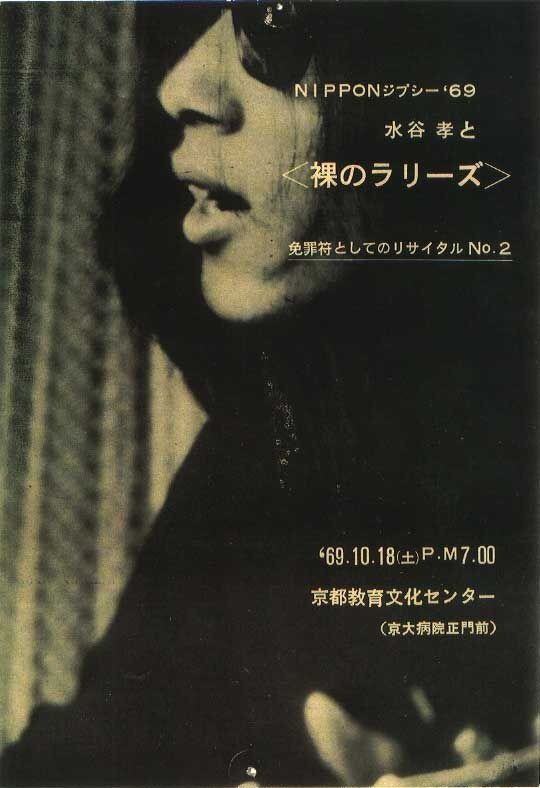

Les Rallizes Dénudés gig flyer, 1969

Did Mizutani have all his master tapes? Did his family send them to you?

MK: He had his own room where he stored everything. I got a suitcase full of master tapes, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. These tapes are only the Rivista albums. As well as that, there are many, many cassettes and open reels in his room, in Kyoto, and they are unorganised.

Is that an unreleased recording archive? Like Prince!

MK: We should take time to sort through them one by one, but I have my own projects. I’m telling everybody I need 48 hours a day, 24 months a year! Seriously! I have a few other projects halfway done, there are so many interesting things, and suddenly this monster from 50 years ago has come back to life! [laughing]

I read an interview with you, and you said even though it was a basic setup, doing the Mizutani recording was the first record you ever produced.

MK: I wasn’t really sure because you know, we were totally amateur. I had never done a concert either. I was just playing in my room and using two tape recorders and dubbing. I think we did an okay job. Before my time there was of course an original Rallizes, a couple of guys – one of whom was very radical. Well, we were all basically radical.

But one perhaps more radical than the rest?

MK: One who cannot come home again… sorry about that. Mizutani disbanded Rallizes one time in 1969, and then started talking to me about starting something new. We jammed together in his little flat and that was the time for me to start into the rock & roll world.

Mizutani, the album you recorded is, is one of my favourites, but can you tell me what you remember about that session?

MK: We had started jamming together in his little flat in Kyoto, smoking and playing guitar. Probably for a few months we kept doing that. Then he booked a studio at Doshisha university for one night. We went in with our instruments and a little amp. There were two mono-reel/ open-reel tape recorders, and I knew what to do because I was doing similar things in my own place. I was living with my grandmother, and I had my own room where I was doing home recording all the time. Some songs I did maybe three parts: guitar, bass and some xylophone or glockenspiel. One guy is just playing a little handmade percussion to keep the tempo, and Mizutani mostly playing guitar and singing.

How long was the session?

MK: Overnight? I don’t remember what time we started. But probably until 9 or 10am. It was morning, bright outside when we came home.

How much were you writing on the spot, and how much was material you had written before the session?

MK: We fully prepared before we went into the studio, and I had been doing sessions in his little flat, which was when we did the songwriting. With some songs I would start playing chord progressions and he joined with the vocal. He played guitar too and he maybe hummed and composed lyrics. We did sessions like this for a few weeks and then booked the studio, so when we went to the studio we knew what we were going to do. It was all night. But you know I never thought this little tiny demo recording would live so long and spread worldwide. I never thought about that.

If you had, it would never had happened.

MK: I had a very bad cassette copy [of the session]. After that, I played it back many times, but the tape was so bad I didn’t know how well we were playing or how well the recording was done. I had no idea. The songs were interesting, and I like the recording. I like the feel of it.

It’s very tender in parts, you know?

MK: Yeah, we were tender! We were so young. So genuine. I have received the master tapes and in there I found the little 7-inch reel that was the exact tape I recorded on that night, the original.

What year did you leave Rallizes officially? How did your time there end?

MK: I played with Mizutani from late 69 till August 1970. And I returned in 71 and played ’til maybe end of 1973. I’m not sure exactly when my last gig was. I started gigging with Sunset Gang in 1973 with Shunichiro Shoda, the drummer of Les Rallizes Dénudés. When Sunset Gang became busy I quit Les Rallizes Dénudés.

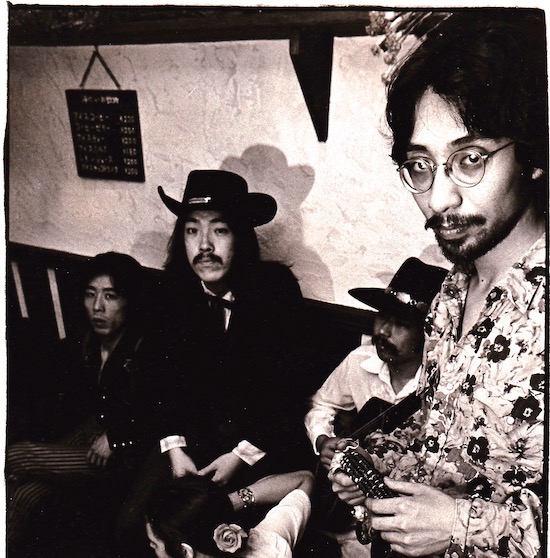

Sunset Gang

For me, because there was so little information, this band is always just about the music – Mizutani has passed away but the music is still the same.

MK: I’m so glad that his pureness penetrates the world. And you can’t even hear what he’s saying, you know? For you it’s a foreign language, with lots of echoes, but still people can feel something, some pureness and some seriousness. I’m so happy I could help him like this, but I was too late. When we had the two months’ of frequent conversation we even made plans to do a world tour, and do a final Budokon concert together, he even asked me if Hosono could join.

Haruomi Hosono?!

MK: Yeah! I was so surprised. It would mean that I had lost my job! [laughs] I loved playing bass for him but rhythm guitar? Not so much fun. The next day I phoned Hosono and said, ‘Mizutani says that he wants you to join’, he said yes instantly.

When you spoke to Mizutani most recently did you talk about what, what he wanted for his music? Did he think about listeners or audience or legacy?

MK: Musicians never talk about that. We don’t expect, we just play and record and feel bad. [laughing] Some shoot heroin, some drink. We’re very poor animals. We never plan something bright for the future. Mizutani is an extreme, extreme cat. He only minds how he plays and how his guitar talks. He never thought about the audience. He minds how he looks; he was a chic looking guy, an extremely beautiful animal. Of course, the industry was nothing to him.

This is why I wanted to talk to you, because some information in English is a bit… mysterious.

MK: I know! Total mystery! I even heard, hey, Mizutani made big money selling this and that – all wrong.

Was Mizutani receiving any income from music at the end?

MK: Not at all. I never really discussed it with him. The music ended up pirated again in 2011, [he] didn’t even know. It’s too heartbreaking to discuss. But anyway, those Rivista recordings are the official releases, and Mizutani was totally responsible for the productions. Now Mizutani has left the world, but this is the start of a new day for Rallizes.

Did he know about the size of Rallizes’ international audience that had grown up over the years?

MK: Only after his last show at Club Citta in Kawasaki in 1996. At that time, there weren’t so many foreign fans, only a few who lived in Japan in the 90s. Otherwise it only started happening this century, after 1999, 2000. What was the first bootleg in Europe? 1997 maybe? I remember somebody showed me that Mizutani album on vinyl, and I was shocked – hey, this is me! I thought about buying it, but it was $50, so no way. After that there were many CDs. His music spread like crazy this century and he knew that – he was monitoring in some strange way. I said, I’ve met all these young musicians aged 30 or 40, in America, and they all ask me similar questions. It seems that he was okay about that – nothing really excited him – but maybe it helped him to start thinking about doing the last tour. The world was waiting. All the kids who have never seen a Rallizes performance before, but they are in love with this music, and they know everything. I said that it was time we started thinking about something, and he said, yeah, agreed. There was a good mood, and we had frequent conversations, and he was so passionate. Somebody told me this rumour that he got ill one time, but we never talked about that, I didn’t need to know. On the phone Mizutani sounded so alive and talked clearly – that was all that I had to know. He was totally okay on the phone. At some point, he disappeared again, around end of September or early October [2019], a little over two months before he passed. I didn’t know – nobody told me. This information wasn’t told to anybody. So that’s why I did some interviews in May last year – I said I got a good conversation with Mizutani going but he’s gone back to the other side of the mirror: he’s disappeared. I was waiting, but there was a reason for that – he had passed away.

So the last time you spoke was in 2019?

MK: I lost contact, and he never replied to my phone and text. So I assumed that something had gone wrong. But that’s him. That [is the sort of thing that] could happen. He was a difficult man, very moody, so I thought, ‘Okay, let’s wait and see if he changes his mind and starts feeling more willing.’ Instead, the family phoned me up asking to meet and discuss what should be done.

Where was he living?

MK: He passed away in Kyoto. He lived in Tokyo for a long time [and was moving] back and forth, and somewhere in France with a relative.

Les Rallizes Dénudés

Having played in different bands, having done production and everything else, when you look back now, how do you think the that early experience with Rallizes influenced you?

MK: This was the start. It was like elementary school. If you don’t pass that school, you never go to the middle school! It was education number one, for me. Before that, I was totally amateur. With Mizutani I learned everything, musically. He was only a couple of years more experienced than me, he started in 67. And I joined in 69. For me Rallizes was my first experience of being in a band and leading a musician’s life. I was so lucky to meet him.

In what way was that the beginning for you?

MK: I was playing in a bossa nova band before that. I was a jazz kid. From my mid-teens my idols were Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins. I was listening to other things like Ray Charles, Billie Holiday, but when I started playing music by myself, jazz just wasn’t my thing, so I picked up Brazilian music and formed a band. It was really amateur, I was just 18 years old. But I was lucky to have very good guitar player and a good singer, I was playing flute and singing a bit and did arrangements for about six months to a year. When I met Mizutani, I became totally rock & roll: part of the revolution. I had never heard Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane before that. He played all the San Francisco bands, ESP, records from New York, Velvet Underground, then The Stooges and stuff like that. I said, ‘Wow, this is a whole new world.’ I knew about Woodstock, but the movie wasn’t completed in 69 of course. We met a few months after that. I think I saw the premiere of the movie in America, not in Japan. I left Japan in September 1970, and when I was visiting America he moved to Tokyo. I came back to Kyoto and finished school – around that time we were all moving around between Kyoto and Tokyo. Eventually I moved to Tokyo too, I had a girlfriend I started living with. Then I was gigging with the band, and at the same time – at the Oz club – I started playing with my own group, Sunset Gang, with the same drummer, who was very good. We got along very well. We became fairly popular and we started touring, then we got a record deal. I did several albums with a couple of different record companies, and in the 80s, again I did different projects and started gigging worldwide, touring Europe. Opening for Japan, the band.

You opened for all sorts of people didn’t you?

MK: INXS sent a telex – no fax at that time, no email – to the record company, saying that we were invited to their first major tour in Australia in 1984.

I read that you went to some really legendary shows in America – The Band at the Last Waltz and Grateful Dead at a Black Panther Rally, among others.

MK: Oh, yeah. I saw all the all the big bands at that time, 1970-71. But I had that feeling when I started listening to American rock & roll that I had to be there – that it wasn’t just for stereo audio, it was more than that – more energy and spirit. So I started planning to go to America. We discussed that I would stop gigging with Rallizes for a while, but when I got back from the States, maybe I could re-join. So that’s what I did.

Did Mizutani not want to see these bands as well? Why did Mizutani not leave with you?

MK: I don’t know, maybe he was too busy, I never really thought about it. It was only me who listened to the music and thought I had to be there. I’m a five times carnival survivor from Recife, Brazil. I saw this movie called Antonio das Mortes, a revolutionary movie at that time about folklore, history and everything. I was so touched, and after 30 years this movie was still in my mind. So after Hosono and I recorded as Harry & Mac in 1999, I started thinking this was the time to go. Once I went to Pernambuco – this centre of original carnival – I got completely hooked. And I went five times, every year. I did everything to make enough money to keep going back. So this is me – if I feel something, I must go there.

That US trip was my first sort of trip. I felt the frequencies and spent seven months in America. A few weeks before I left Japan, [Mizutani] gave me all the information in handwriting. This I will publish in December in a Japanese magazine.

Was this a letter to you?

MK: It’s a notebook. He wrote all the information about things he wanted me to do. He wanted me to see bands: Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane. I knew all the bands, of course, but he wanted to make sure, so he made this big memo, saying I must see these bands, and please buy these records and bring them home. It listed all his influences. People will see the list in his own handwriting. I was wondering if I should do that, but I asked a close relative, and they said we should. It’s a little embarrassing maybe, his handwriting is so cute.

At that time, did you know you wanted to work in music for life at that time?

MK: No, no, no. I was so enthusiastic, and this was a time of revolution. I didn’t know what I was going to be. Until 69 when I was playing in the bossa nova band, I knew I would graduate school and join a company, probably a big advertising agency. That’s what I was planning; what I was thinking about for my whole teens, but after 69 and meeting Mizutani, and touching all this revolutionary rock music, I had no idea what I would be, so after I came back from America, I was totally a revolution child. So, I re-joined the band, and about six months after I was arrested for growing marijuana and giving it away. It was party, party, party.

Sunset Gang, portrait by Aquilah Mochiduki

Japan has very different attitudes to drug use than UK and America, did that affect things for you?

MK: This was a very rare case – a 21 year old college kid growing marijuana. It was unusual. Anything to do with drugs is usually Yakuza or gangsters, but I didn’t do it for money. I did it for, I don’t know – enlightenment? Self-education? Without this experience I don’t think I would have become a sound engineer.

What did Mizutani and the band think of that at the time? Did you have to leave the band because you got arrested?

MK: I re-joined the band again, I took off for two months and came back to the band and started playing again. No problem. Mizutani even made jokes about it. And also, he knew why – he was like a detective who gave me all the information on why I got screwed. It was so funny.

What do you mean, like, in terms of you did this wrong? You did that wrong?

MK: Something like that. You know, half-jokingly, you know. This is not really serious thing, but it’s not a full joke either. He’s so cool, he’s like my brother. He watched me and told me these things.

How does it feel and how does it sound to you, coming back to this music again recently, after from the beginning of your life in music.

MK: It’s half a century ago, almost. I am simply amazed that we were right. I wasn’t sure. I was so amateur and so inexperienced. I didn’t know what we were doing, but I’m amazed how right what we were doing was. Nobody told me what to do, it was all our discovery; discovering ourselves. We were never really educated musically, we never went to music school or anything, but listening to Oz Days again, I thought, ‘Wow… This is a very unique, one time only thing.’ Especially his guitar of course, and I was playing bass very hard. One song called ‘Otherwise My Conviction’ it’s kind of a fast song with the tempo, but the style was like punk rock, in 72! What was that?! It’s psychedelic music, influenced from Velvet Underground, The Dead, Stooges. MC5 was a big, big influence. But in 72, not many people played that music. Especially like that song – we’re playing so hard. Mizutani really liked Detroit stuff like MC5.

It’s good to hear that there’s communication between you as a former member of the band, with the family, all working together.

MK: Well, I can’t talk to Mizutani anymore. Although I almost feel like Mizutani is sitting next to me now, many times I really felt that.

Is the is the next time there’ll be any more information is on December 11?

MK: Yeah. On the website. We will also have a release party next year, but it will be a gig to introduce the new album in some venue, no band, but I will try to have similar audio set and light shows from his last concert. I’m checking if the technicians are available, so kids who have never seen a Rallizes performance can come to the venue and feel the atmosphere, and feel the volume, of how loud the band was.

Which brings us to live shows. Just how loud was it back then?

MK: Well, you know, for English people it was medium [laughing]. I was listening to all the punk bands in the early 80s and Siouxsie and the Banshees was just something else. Even the club Ministry of Sound, these places were super loud. Compared to that, it’s not louder. We only have 100v [line speakers], and you have 250v or something, so you can be the loudest in the world! We won’t be able to be that loud next year. But it will be the loudest party in Japan! I will try my best. The first Rallizes concert I went to in 69 was my first loud rock & roll experience. He gave me some tickets, and I went there and opened the door and came straight back out. I could not go into the venue because it was too, too loud. It hurt my skin. This was my first experience with loud frequencies. I had to get out, take a deep breath, and went in again.

And then what happened?

MK: After that, I was hooked on the noise.

What will happen from here with the new release?

MK: Probably in March or April. We’ll do the party for the kids to come and feel the Rallizes vibe. After that, other projects of mine are waiting.